The Origins of Traditional Incense in China

Long before incense became a refined art in Japan, it had already flourished for centuries in China.

As early as the **Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE)**, archaeologists found evidence of aromatic woods and herbs burned in rituals.

By the **Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)**, incense was deeply woven into daily life—as medicine, meditation aid, and ceremonial tool.

Monks, doctors, nobles, and scholars all used it to regulate qi (vital energy), focus the mind, and purify the body.

During the **Sui and Tang dynasties (581–907 CE)**, Chinese incense culture became highly developed, incorporating:

- Complex **herbal formulas**, guided by traditional Chinese medicine

- The principle of **Jun–Chen–Zuo–Shi** (chief–deputy–assistant–envoy)

- Specific techniques like roasting, grinding, aging, and blending to reduce smoke and enhance aroma

This wasn't perfumery. It was a form of **natural therapy**—carefully calibrated, deeply ritualistic, and rooted in health and harmony.

---

1. Incense as a Cultural Export: The Story of Monk Jianzhen

The **Tang dynasty (618–907 CE)** was a golden age of Chinese diplomacy and soft power. Through the Silk Road and maritime routes, Buddhism, tea, poetry—and incense—reached distant lands.

One of the most important cultural ambassadors was the monk **Jianzhen** (known as Ganjin in Japan).

In **753 CE**, after five failed attempts, Jianzhen finally reached Japan. He brought not only Buddhist texts and medical knowledge but also:

- **Incense-making tools**

- **Herbal incense recipes**

- A deep understanding of incense as a spiritual and medicinal craft

Historical records suggest Jianzhen introduced **Chinese incense formulation techniques** to Japan’s elite circles. This became the foundation upon which the Japanese **Way of Incense—kōdō—was built**.

---

2. China's Influence on Early Japanese Kōdō

During the Nara and Heian periods, Japan actively imported Chinese culture, especially Buddhist traditions. With them came:

- **Chinese incense woods** like aloeswood and sandalwood

- Techniques for **blending and aging incense**

- Rituals for appreciating fragrance in a meditative state

Early Japanese incense manuals, like **Kō no Ki (The Record of Incense)**, were directly inspired by Chinese incense philosophy.

The practice of **“listening to incense” (monkō)**, where participants guess subtle scent notes, evolved from Chinese scholarly incense gatherings.

---

3. Two Cultures, Two Paths: Function vs Aesthetic

While both traditions started from a shared root, their goals gradually diverged.

- **Japanese kōdō** became an art of refinement—focused on poetic naming, memory, and aesthetic subtlety

- **Chinese incense** remained medicinal and functional—designed to heal, harmonize, and restore the inner body

At Herimyst, we respect both traditions. But we are especially inspired by the **Chinese approach**, where incense is not just a scent—but a **ritual for balance, rest, and inner clarity**.

---

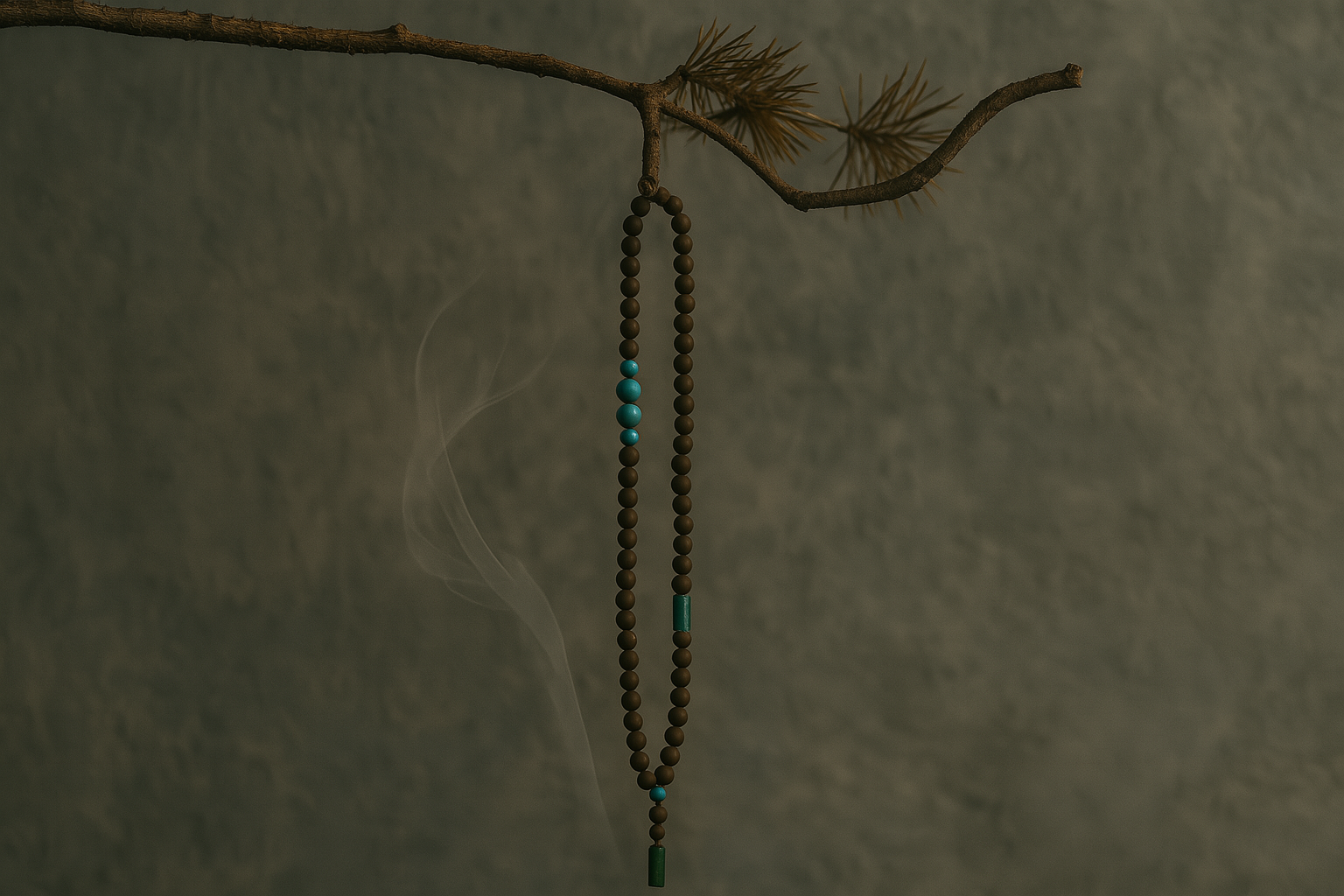

4. Herimyst: Reviving the Ritual

Most modern incense is made from **synthetic fragrance oils, dyes, and chemical fillers**. It’s fast, cheap—and disconnected from heritage.

At Herimyst, we return to incense as it was meant to be:

- 100% **natural herbs, resins, and woods**

- Blended according to ancient Chinese formulas

- Crafted in small batches by hand

- Inspired by monks like **Jianzhen**, whose legacy we carry

We don’t just make incense.

We make **moments of mindfulness**—rooted in thousands of years of wisdom.

> Incense once crossed oceans with monks and merchants—not for decoration, but for healing and connection.

> Herimyst follows the smoke back to its sacred source.